When Morgan Neville’s documentary “Roadrunner” appeared in 2021, many film critics seemed to take a greater interest in the filmmaker’s ethics than the story he told about the late chef Anthony Bourdain.

At issue was Neville’s editorial decision to use AI to recreate Bourdain’s voice as a narrator, transforming something Bourdain had written into something he said. In so far as documentary films are supposed to be, at their core, non-fiction, some believed that Neville had crossed a line. He created audio that isn’t real. He made Bourdain speak words that he never actually said aloud.

“We can have a documentary-ethics panel about it later,” Neville told the New Yorker, seeming to blithely dismiss concerns.

In an interview with GQ, Neville claimed he had been given permission from Bourdain’s widow to use AI in the way he did. Ottavia Bourdain publicly denied this.

While some might criticize Neville’s behavior as dishonest or unethical, doing so would be a mistake—because it presumes that the field of documentary filmmaking has standards around ethics and honesty. It doesn’t.

As the podcast “On the Media” reported in its 2017 examination of this problem, “Who ensures that films hew close to the reality they claim to depict? In the documentary world, it’s individual filmmakers working alone, without a clear rulebook, and with only their consciences as their guides.”

This ethical vacuum, in recent years, has presided over increasingly questionable editorial behavior by documentary filmmakers—and the streaming platforms that host their work—including a proliferation of conflicts of interest. Unbeknownst to viewers, much of the documentary content we watch today may actually be advertising, as private, wealthy actors—from Big Food to Big Pharma—hire top documentary filmmakers to tell their stories and promote their brands. These one-sided and often sophisticated propaganda films are presented to paying viewers as independent, and sometimes even journalistic, documentaries.

One fast-growing segment of this genre are so-called ‘bio-docs’ about celebrities.

“No documentarian wants their work to be confused with ads, but all documentarians need access,” IndieWire reported last month, explaining how filmmakers often “partner” with their celebrity subjects. Streaming platforms today are larded with celebrity bio-docs, many of which seem to actually be auto-bio docs, if not brand management for wealthy and powerful public figures. IndieWire reports that bio-docs are nearly four times more numerous on streaming platforms today as they were in 2020.1

Many top filmmakers are jumping on the trend. Three weeks ago, Academy-Award-winning filmmaker Morgan Neville released a long, glowing documentary series about Bill Gates on Netflix. And tomorrow Neville will unveil a bio-doc on Pharrell Williams—after Williams approached him to help tell his story.

It would be easy to dismiss ethical questions about bio-docs blurring the line with advertising—on the assumption that these films are being consumed by the public as puff-pieces, not serious or independent documentaries. But the reality is these widely watched films are changing the way we think about the world. They’re allowing the rich and famous to launder their reputations in ways that brainwash the public—rewriting history, distorting reality, and reframing public debates.

********

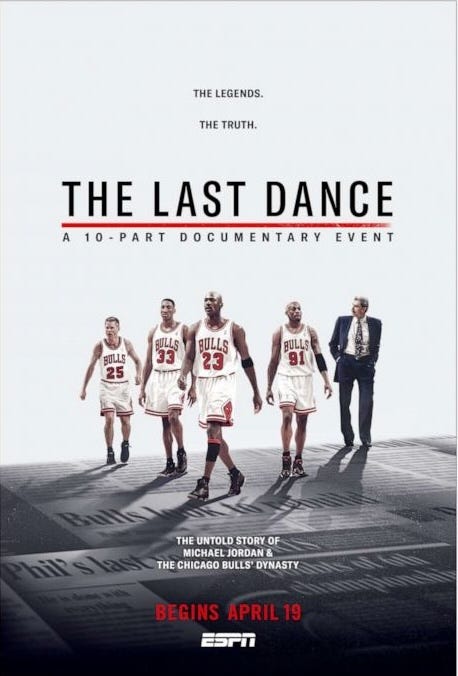

In 2020, documentarian Ken Burns made waves when he sharply criticized the wildly popular ESPN/Netflix docu-series, “The Last Dance,” which profiles the 1990s Chicago Bulls basketball team. Burns was upset that the filmmakers partnered with basketball player Michael Jordan to tell the story, something Burns said he would “never, never, never, never” do—for ethical reasons.

“It means that certain aspects that [Jordan doesn’t] necessarily want in [the film] aren’t going to be in, period,” Burns told the Wall Street Journal. “And that’s not the way you do good journalism.. . .and it's certainly not the way you do good history, my business.”

Burns wasn’t the only one upset. Several of Jordan’s former teammates, who appeared in the film, accused the docu-series of glorifying Jordan at the expense of everyone else—and at the expense of the truth. “The Last Dance’s” story wasn’t just unfair, but it created an alternate reality of what the Chicago Bulls dynasty really was.

“The producers had granted him [Jordan] editorial control of the final product. The doc couldn’t have been released otherwise. He was the leading man and the director,” former Bulls player Scottie Pippen wrote in GQ.

Another of Jordan’s former teammates, Horace Grant, had a similar reaction. “When that so-called documentary is about one person, basically, and he has the last word on what’s going to be put out there,” Grant said in 2020, “it’s not a documentary. It’s his narrative.”

These three sources—Burns, Pippen and Grant—are making the same fundamental point. Once a filmmaker gives their subject editorial influence, the film arguably becomes more of an advertisement than a documentary.

Yet audiences seldom are positioned to thoughtfully consider the vested interests behind the documentaries they watch—because filmmakers and streaming platforms don’t clearly disclose them. One widely published graphic promoting “The Last Dance,” for example, describes the film as offering audiences “The Legends. The Truth.”

Jordan’s behind-the-scenes role in “The Last Dance” is not noted anywhere in the film or in the final credits that I could see. Only when I Googled the names of the producers listed in the credits did I find a link to Jordan (several appear to be his business associates).2

If anything, “The Last Dance” appears to purposefully present itself as independent, journalistic and truth-telling—-for example in its storytelling approach of seeking out different versions of the same story from different sources. The film also seems to put Jordan in the hot seat at times, including asking him about his reputation as a bully. Nevertheless, the docu-series invariably delivers a narrative that levitates Jordan. (Notably, “The Last Dance” also seems to amplify Jordan’s business interests, including an extensive profile of his lucrative relationship with Nike.)

Similar ethical questions can be found in Morgan Neville’s recent five-episode Netflix bio-doc, “What’s Next: The Future with Bill Gates.” The filmmakers present the series using words like “independent” and “investigative," and the bio-doc trades in the same kind of journalism theater as “The Last Dance”—taking on a patina of objectivity by occasionally putting Gates in front of critics.

In one very short scene, Gates, a multi-billionaire, sits down with Senator Bernie Sanders, a political crusader against extreme wealth. Gates acknowledges to Sanders that the wealthy should pay higher taxes. Nearly a dozen news articles went on to report Gates’s comments, presenting him as a progressive voice on taxation. This seems quite misleading given the many critiques Gates faces around tax avoidance—which the bio-doc studiously avoids.

The result is a kind of misinformation—misinforming audiences (and the news media) not just about Bill Gates but also about vital political questions, like how we organize our economy and address inequality. Ironically, the Gates-Netflix bio-doc devotes an entire episode to misinformation, presenting Gates as a victim of conspiracy theories.

In another episode, Neville and Netflix give Gates ample space to promote nuclear energy as a key solution to climate change—and even to promote the nuclear company he launched, TerraPower. Missing from the story are the voices of high-profile scientists who sharply criticize Gates’s climate solutions, and the experts who cite safety concerns and public risks with Gates’s nuclear ambitions.

Few viewers will take the time to assiduously research the names that appear in the final credits, but if they did, they would realize that one of the film’s producers appears to work for Gates. This (and other evidence I uncovered) strongly indicates that Gates was a partner on the bio-doc, not simply an interviewee. Asked to clarify Gates’s financial and editorial roles, Neville, Netflix and Gates all refused to respond.

One of the more bizarre bio-docs streaming right now on Max is “Wahl Street,” which profiles actor Mark Wahlberg’s entrepreneurial activities outside of show business.

Watching the series, it quickly becomes apparent that no matter which of Wahlberg’s investments are being profiled, Wahlberg is the brand. And that includes “Wahl Street,” itself, which Wahlberg produced. The series seems to have been a success; Max picked up two seasons, 16 episodes in total.

The bio-doc extensively covers Wahlberg’s work with his fledgling documentary production company, Unrealistic Ventures. But these scenes, as I watched them, never make explicit that Unrealistic Ventures is also the production company behind “Wahl Street.” If audiences stick around for the final credits, they might (or might not) connect the dots.

The bio-doc appears designed to impress viewers with Wahlberg’s industriousness or inspire them to check out his clothing line, Municipal; his gym franchise, F45; and his restaurant, Wahlburgers. At a point, however, it’s hard to avoid asking: why are streaming platforms asking us to pay monthly subscription fees to watch what seem to be, essentially, ads for Mark Wahlberg, Michael Jordan, Bill Gates and other celebrities?

And where is the independent docu-series looking into Wahlberg’s history of racist hate crimes? Where is the docu-series that takes an independent look at Jordan’s toxic reputation as a bully? Where is the MeToo docu-series profiling the allegations of misconduct Bill Gates faces? Where are the voices of the experts who say the Gates Foundation should pay reparations for all the harm it has caused?

And where are the ethical rules that govern the field of documentary filmmaking? In so far as filmmakers claim to be telling non-fiction (true) stories, and in so far as Big Streaming presents the content to subscribers this way, where are the rules that protect paying audiences from becoming dupes? Where are the disclosures or warning labels that allow viewers to easily distinguish advertising from documentary filmmaking, branded content from independent content, fiction from non-fiction?

A more structural question to consider is: who benefits? Is the reason we’re seeing an explosive growth in bio-docs because the public is clamoring for celebrity puffery—and has no interest in documentaries that independently examine and expose the rich and powerful? Or is it possible that Big Streaming is pushing bio-docs because they are so profitable—because they are cheap to acquire and easy to promote?

As one advertising executive noted in Fast Company in 2016, talking about the ways documentaries can function as advertising, “Usually we pay for eyeballs in advertising, but here you have people paying money to see it . . . That’s an ah-ha moment.”

One obvious way to address these ethical problems is to hold documentary filmmakers—and the tech companies that platform their work—to the same ethical standards as news rooms and universities that engage in non-fiction storytelling. No serious, ethics-bound journalist or historian, for example, would partner with a super-wealthy public figure to tell their story, then present the work to the public as a totally independent account. And if a writer were discovered to also be financially partnering with the subject of their reporting, this could destroy their career or permanently brand them as sell-outs.

Of course, things might also turn out differently. Both journalism and academic research, despite having long-standing ethical rules, are hotbeds of bad ethical behavior. This includes the same kind of undisclosed conflicts of interest we see in documentary filmmaking.

Here’s the difference: we can compel news outlets and academic journals to address these ethical failings because there is a shared understanding of what the ethical rules are. My own investigations have compelled numerous outlets to belatedly disclose dozens of financial conflicts of interest, including in highly prestigious publications like the New York Times and Nature. I wouldn’t be able to ask an editor to address an ethical problem, however, if I couldn’t point to an ethical code of conduct that they violated.

This is the gray space in which documentary filmmakers play. Efforts to reach out to the filmmakers and streaming platforms mentioned in this article generated no responses—which is maybe not surprising. These outlets can’t be held accountable to ethical rules that don’t exist.

Creating an ethical code—or simply applying the code that already exists for journalists— is an obvious and important first step toward cleaning up documentary filmmaking. One ethical guideline from the Society of Professional Journalists seems particularly germane: “Distinguish news from advertising and shun hybrids that blur the lines between the two. Prominently label sponsored content.”

Having ethical rules is only a starting point, however. We also have to have a mechanism to enforce the rules. There needs to be consequences for bad behavior and abuses of power.

A potentially potent intervention, which I’ll explore in detail in the next installment of this investigative series, goes beyond non-binding ethical rules. In so far as we, as a society, have created a variety of laws to protect paying consumers from unsafe products and practices—why don’t we have legal rules in place to protect paying viewers from being brainwashed by the questionable content that Big Streaming presents to us as independent storytelling?

It turns out such rules might already exist. Stay tuned for the third part of this series. And if you missed part one, check it out here:

The only way that I can keep producing reporting on this platform is with your support. If you can afford to support my journalism, I’d greatly appreciate your help. Can you help me reach my goal of 50 paid subscribers? (If you can’t afford to do so, subscribe unpaid.)

Parrott Analytics told me that bio-docs currently represent 1.4 percent of “all streaming original series,” down from a high of 2.4 percent during the pandemic. This drop may be because so many celebrities already have bio-docs, and filmmakers are running out of new material. As IndieWire notes—-at this point, “who hasn’t had a documentary?”

One credited producer, Curtis Polk, is often described in the news media Michael Jordan’s business partner and “right-hand man.” Another producer Estee Portnoy appears to be a long-time business associate of Jordan. Elsewhere it’s been reported that Jordan’s production company, Jump 23, was involved, but I didn’t see this listed in the credits anywhere.