Diplomatic immunity for Gates in Kenya

New rules treat the Gates Foundation like a sovereign state, Bill Gates like a king

While nations around the world have long treated Bill Gates as a head of state, it’s now been practically codified into law in Kenya.

Last week, the government announced that the Gates Foundation—and its “servants”—would be granted diplomatic immunity, a privilege normally given to foreign officials, like ambassadors. The foundation’s new ‘special status’ includes “immunity from legal action for acts done in the course of official duties,” according to Kenyan news reports.

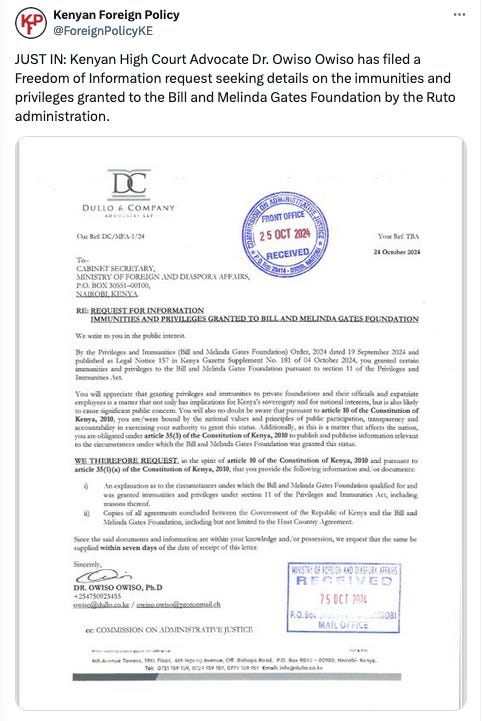

Across the nation, the decision has raised alarm bells. One public advocate petitioned the government for documents undergirding its decision, noting that Gates’s diplomatic immunity has “implications for Kenya’s sovereignty and for national interests.”

Outside of Kenya, many worry that the decision will create a domino effect, as other nations are pressured to follow suit, offering immunity to Bill Gates’s private foundation to entice the billionaire to direct more resources into national social programs. Kenya’s decision could also set a broader precedent for allowing other billionaire philanthropists to secure, or demand, legal immunity.

Gates’s diplomatic immunity comes just weeks after farmer organizations and religious leaders across the African continent called on the foundation to pay reparations for the damage it has caused through its interventions in African agriculture, as reported in Forbes and The Continent.

Daniel Maingi, coordinator for the Kenya Food Rights Alliance, believes the Gates Foundation, working with its corporate partners, now has a license to test out new technologies in Kenya—with impunity— under the banner of charity.

“Gates, himself, has been walking into Kenya—in and out like it’s his kitchen,” Maingi told me. Now that the foundation enjoys a level of immunity under the law, Maingi says, “Kenya becomes the testing ground…That is a big, big concern. It’s a big red flag.”

Kenya has long been a testing ground for Gates’s high-tech interventions, and serves as the home base of Gates’s most important, and most embattled, agricultural project, AGRA—to which the foundation has given at least $872 million. A political organization, AGRA boasts having worked on 68 policy reforms across the African continent, aimed at expanding a technology-driven model of farming that uses new seeds and agrochemicals. Independent research shows that these interventions have failed; in some places, Gates’s work has actually presided over an increase in hunger.

Because Gates’s diplomatic immunity appears to broadly apply to all of its work in Kenya, Maingi believes it also covers the work of AGRA. It could also cover the work AGRA does with corporate partners, which have historically included Bayer, Syngenta, and Microsoft (which Bill Gates co-founded).

“In terms of food sovereignty, as we give Gates these privileges and immunities, Africa is going to be——not food sovereign, not seed sovereign—- we’re going to be slaves and masters of the big corporations,” Maingi told me.

This critique speaks to the way that Gates’s charitable interventions often work through corporate partnerships and often focus on technological interventions and commercial commodities. This work has long drawn criticism around conflicts of interest, for example in 2010 when activists uncovered that, while the foundation was pushing African farmers to adopt GMO seeds, the foundation also had financial investments in GMO giant Monsanto (now owned by Bayer).

The larger concern Maingi cites relates to “ethics dumping”—the Gates Foundation conducting research trials in poor nations that would not be allowed under the rules and regulations of wealthy nations. The foundation has many times been accused of such behavior. Activists and scholars, for example, have long raised questions about a Gates-funded malaria intervention program involving genetically engineered mosquitoes, citing problems with informed consent and conflicts of interest.

Activists and scholars have also challenged the ethics of Gates’s circumcision campaigns. These campaigns, including in Kenya—an attempt to reduce HIV transmission—have raised sharp critiques around colonialism, as African bodies are instrumentalized in service to the goals of Gates and other wealthy funders.

Maingi points to a controversial philanthropic project the foundation funded in India a decade ago with HPV vaccines, which raised questions related to research ethics and human rights. The scandal generated international news coverage. As I reported in my book, “The Bill Gates Problem”:

During the course of the Gates-funded HPV demonstration project in India, seven school-age girls died, prompting the government to shut down the trial. A government investigation found that the study had failed to get proper consent from the parents of underage schoolgirls. The researchers had also not set up an adequate reporting mechanism for harmful side effects related to the vaccine. The government stated that the deaths were not related to the vaccine, but questions continued to surface when it was reported that no autopsies had been conducted.

The alleged ethical missteps in the Gates-funded study unleashed a major backlash, with public health professionals accusing Gates’s partner, PATH, of using Indians as “guinea pigs.” A parliamentary inquiry condemned the study as a “blatant violation by PATH of all regulatory and ethical norms.” It also cited the appearance of financial conflicts of interest …Noting the “monopolistic nature” of the HPV vaccine—controlled by Merck and GSK, which donated six million dollars’ worth of vaccines to the Gates-PATH study—the parliamentary report described a “well planned scheme to commercially exploit a situation” through “subterfuge.”

…The fallout from the scandal may have created public distrust in Indian medical regulators. Public health experts noted at the time that the HPV uproar would make it harder to do clinical trials in India. This, in turn, could make it harder to bring new lifesaving drugs to market.

The Gates Foundation and its partner, PATH, deny any wrongdoing, but you can read more details of the scandal in my book——or in accounts published by Science, the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, and other legal scholars.

To be clear, the moral of the story here is not that the HPV vaccine, or any other vaccine Gates works with, is bad or dangerous or kills people. Rather, the moral of the story is that the Gates Foundation has a history of highly questionable, colonial behavior, and this history indicates a need for more checks and balances, not fewer. Giving the foundation even greater unaccountable power, through diplomatic immunity, may have serious, harmful consequences, like driving vaccine hesitancy. Or hurting farmers. Or creating distrust in public institutions. Or eroding democracy.

The Gates Foundation did not respond to my press inquiries, but it did issue a statement in Kenya, apparently in response to growing public criticism. The goal of the response, clearly, is to minimize the gravity of Gates’s new diplomatic immunity, describing it as part and parcel of “the typical agreements Kenya makes with other foundations and nonprofits.”

Yet if diplomatic immunity is so normative and so common, why is the Gates Foundation only now—decades into his history of work in Kenya, at a moment when it is facing calls for reparations—claiming this ‘special status?’ (Also, I found no evidence of any other billionaire foundation having diplomatic immunity in Kenya.)1

To the extent that Kenya does give diplomatic immunity to non-governmental organizations, like, say, relief workers responding to a humanitarian crisis, there is plenty of room to argue that this 1) should be reconsidered or 2) that such examples are categorically different from Gates.

The Gates Foundation is an overtly political organization with far reaching commercial ties and conflicts of interest. It’s not simply trying to solve succinct problems, or empower poor nations to roll out their own solutions; rather, the foundation is inserting itself into the body politic of foreign nations, engaging in nation-building and world-making activities that, over a period of decades, have significant influence on the lives and livelihoods of billions of people around the globe. The foundation is not an innocent, non-profit, humanitarian body. It is a powerful and largely unregulated political actor.

The good news is, a robust, public debate appears to have sprung up in Kenya, with many voicing opposition to the Gates Foundation’s special privileges and immunity.

These questions get to the heart of Gates’s anti-democratic influence and power, which, at least in Kenya, appears to be reaching new levels. No one ever elected or appointed Gates to lead the world—on any topic. Yet through his great wealth, and his money-in-politics brand of philanthropy, he is able to buy a seat at the democratic decision-making table—-and, apparently, also buy diplomatic immunity.

None of Gates’s philanthropic peers—private foundations with multi-billion-dollar assets, like the Wellcome Trust or the Ford Foundation—appear to have diplomatic immunity in Kenya.

I'd say one of the biggest problems with Gates is the way he and the foundation have mapped out and exploited this gray area between private and public power. It's also the problem that the news media basically has no appreciation for. Thank you, Tim.