He built a brand criticizing billionaires. Are billionaires now bankrolling his work?

Rutger Bregman's new non-profit, the School for Moral Ambition, makes it hard to follow the money, but I found donations from the Gates Foundation and other philanthropies associated with billionaires

If you follow the public debate over extreme wealth, you may at some point have heard the name Rutger Bregman. The Dutch writer made a splash at the 2019 World Economic Forum when he publicly condemned the vapid promises of the global elite, righteously calling out the billionaire class’s proclaimed commitment to philanthropy as “bullshit.”

The clip went viral, and in the years ahead Bregman seized on the moment, inserting himself into the growing public debate around extreme wealth and tax avoidance. His popularity as a talking head may have stemmed, in part, from how modest his criticism was.

In a 2019 interview on an NPR affiliate, Bregman made clear that he doesn’t despise every billionaire philanthropist on Earth. Bill Gates, he noted, is a “really, really genuine” philanthropist who is “doing great work.”

Bregman’s nuanced critique helped him gain solid access to liberal media outlets, which, in the years ahead, would help amplify a series of best-selling books he wrote. Book reviewers sometimes describe him as a kind of edgier version of writer Malcolm Gladwell (author of “The Tipping Point” and “Outliers”): the two authors are progressive-ish big-idea men who churn out popular books that are science-y—but that tend to often oversimplify complicated topics, or over-complicate simple topics.

Compared to Gladwell, Bregman may be edgy. But on the wider political spectrum, Bregman appears more like an edgelord.

In a recent appearance on Trevor Noah's podcast, Bregman stopped the conversation at one point to make a grand pronouncement: “I’m actually going to say something nice about billionaires….I don’t think I’ve ever done that before on a podcast.”

Noah and his co-host Christiana Mbakwe Medina delivered the theatrical reaction the infamous critic of billionaires was asking for.

“Uh-oh—Here we go!” the hosts gushed, pumping up the anticipation for listeners.

Bregman’s example? He talked at length about Bill Gates’s world-changing work on malaria, including funding a new vaccine.

"It took a tech billionaire, Bill Gates, to fund the research that changed history,” Bregman effused. “I think someone like Bill Gates deserves an enormous amount of credit."

After the podcast, Bregman clipped this segment and reposted it across his many social media platforms. Clearly, Bregman wanted to let the world know that he is a believer in that strange, rumored creature: the good billionaire.

Bregman’s belief system, however, appears to be more mysticism than science.

A self-described historian—one could question his qualifications for such a title1—Bregman told Trevor Noah’s audience that he learned of Gates’s good works after studying “the history of malaria.”

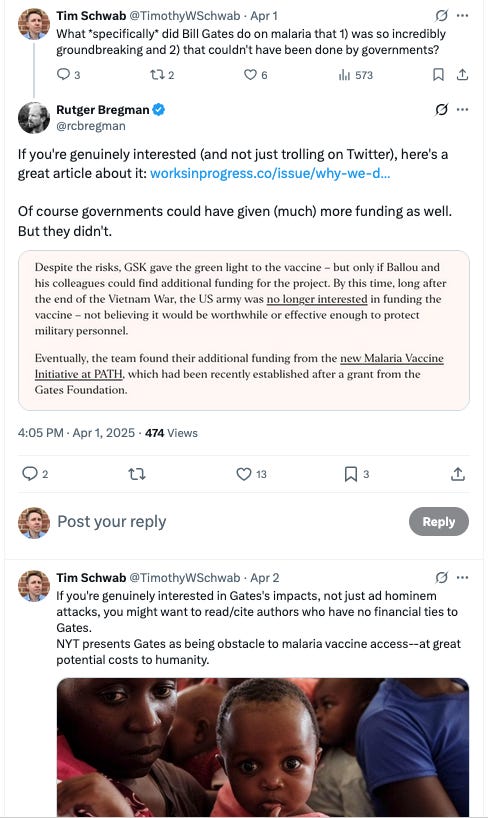

Yet Bregman—even on long-ish social media posts, like LinkedIn—never appears to cite the historical evidence or source material on which he bases his broad and generalized claim about Gates. When I followed up on social media, his first reaction was not engagement, dialogue or debate. It was to accuse me of “trolling.” (In case you’re wondering, this was the first time I’d ever interacted with Bregman.)

See our exchange from X below:

Bregman only offered one citation to support his claims about Gates. Awkwardly, it was to a paper written by authors affiliated with Gates-Foundation-funded institutions.2

Not only is the paper Bregman cites written by conflicted authors—-who are not independent and therefore not particularly credible or authoritative—-but the paper, if you read it, doesn’t clearly or substantially demonstrate Bregman’s grandiose point about Gates’s supposedly singular, history-changing role on malaria.

The bigger problem is what Bregman doesn’t cite—his decision to carefully avoid evidence that does not line up with his conclusion. Said another way, Bregman isn’t engaged in historical research; he’s engaging in historical revisionism.

In our exchange on X, I sent Bregman a New York Times’s article published last year describing the Gates Foundation as actually limiting access to malaria vaccines—arguably at great cost to humanity. How, then, can Bregman so breezily credit Bill Gates with the success of the malaria vaccine? The Times’s article is one of many places Bregman could look to for counterpoints to his one-sided hero narrative.3 Bregman did not respond or engage.

I followed up with Bregman by email, asking if he was familiar with the substantial body of evidence, from highly credible sources, showing the harms the Gates Foundation is causing through its charitable crusades (here, here, here, here, here). The vague response I received—from Bregman’s agent, Anne Strunk—-strongly indicated to me he has never seriously, thoughtfully considered the other side of the story: “Rutger is aware that any major institution faces critique, and he believes it’s essential to engage with a broad range of perspectives. He regularly updates his views based on new information and research.”

With no sense of irony, Strunk then made clear that Bregman would never consider engaging with my own perspective on this issue. (I’m the author of the book, “The Bill Gates Problem: Reckoning with the Myth of the Good Billionaire.”)

“He’s not a fan of your style of journalism, which seems grounded in bad faith instead of curiosity,” Strunk noted in an email.

On social media, some have accused Bregman of the same behavior. On LinkedIn, Dr. Wouter Arrazola de Oñate, who, unlike Bregman, has personally worked on public health in poor nations, including through the World Health Organization, directly challenged Bregman’s distorted view. He also asked Bregman who his funders were. Bregman did not respond.

I initially assumed that Bregman’s fanboy behavior stemmed from his questionable approach to research. He started with the conclusion that Bill Gates must be a good guy, then worked backwards to find supporting evidence—while very carefully avoiding counterpoints.

Another potential explanation was that Bregman had financial ties to Gates—that he was promoting the multi-billionaire in the hopes that Gates would financially reward him or his work in some way. I didn’t expect that to be true. But then I looked. Actually, I stumbled.

Bregman has a new book coming out next week called “Moral Ambition.” Adjacent to the book’s launch, Bregman founded a new non-profit called the School for Moral Ambition, the goal of which appears to be steering upwardly mobile young people into political advocacy on issues Bregman endorses.

The non profit’s glossy, expensive-looking website features a great many photos of Bregman, giving it an almost has a cult-like feel as it extensively promotes the minor celebrity at the center of the project. Bregman’s non-profit group may have a public-facing mission to help others, but the biggest beneficiary is likely to be Bregman himself.

Years ago, Bregman gained popularity for criticizing philanthropy as as a self-serving loophole the rich use to avoid paying taxes, but today his non-profit appears to be openly enticing wealthy philanthropists with promises of tax benefits. This includes directing donors to an online tax-benefit calculator—-which shows that giving 1 million euros to Bregman’s non-profit will generate personal tax benefits in excess of 350,000 euros.4

These massive tax benefits, essentially, mean that the rest of us—taxpayers—are richly subsidizing Bregman’s vanity project. If the public is being asked to help underwrite Bregman’s non-profit, shouldn’t there be, at the very least, some basic accountability around his operations—and some guarantee of a real, public benefit to his work? Shouldn’t we be able to follow the money—to easily discover the names of the donors helping fund his non-profit? The School for Moral Ambition has generated a stunningly large sum of money in its very short existence—$5.7 million to date—but where is the money coming from?

On its website, the non-profit’s FAQs say the group is funded by "a group of morally ambitious entrepreneurs who support our mission.” This inscrutable language carries no hyperlink to a list of funders.

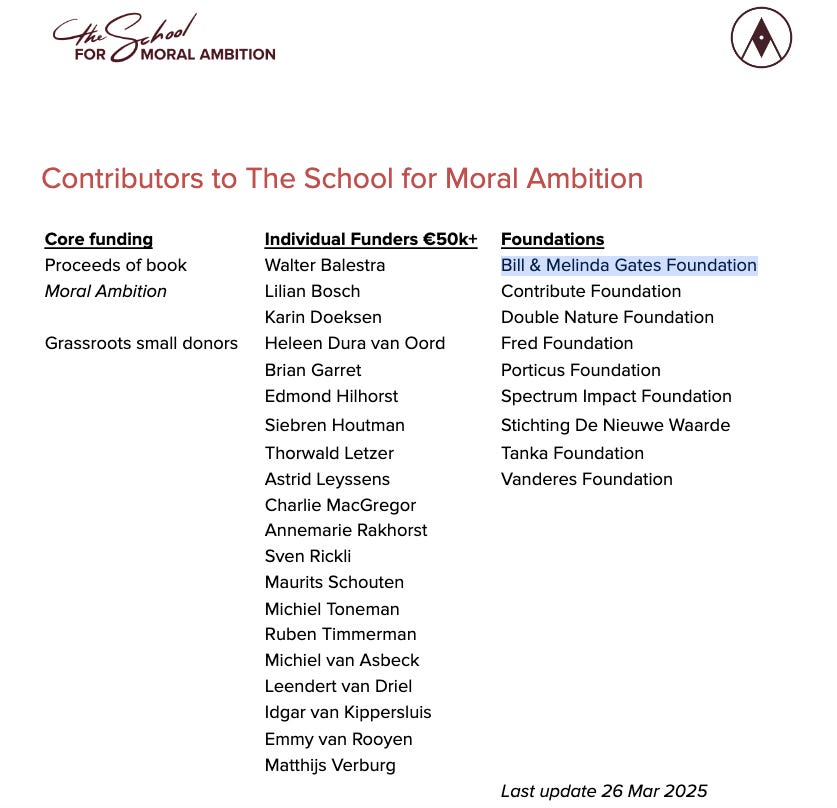

When I followed up with the non-profit, Bregman’s agent, Strunk, directed me to this list, buried on a different web page:

Strunk also made a point to puff up Bregman’s own financial role, telling me, “Our biggest funder is our co-founder Rutger Bregman. Rutger donates all proceeds from his book Moral Ambition (including proceeds from related talks) to our foundation…So far, these proceeds (over one million euros) have funded the launch of our organization and our first programs.”

Strunk said nothing about the personal benefits Bregman may be positioned to take from his donation—in the form of avoided taxes or extremely valuable, tax-subsidized self-promotion.

The bigger contradiction—and ethical problem—concerns transparency, independence and integrity. Or, to borrow Bregman’s favorite word, morality.

Though I had asked the School for Moral Ambition for a list of its funders, Bregman’s agent only gave me a partial list—-and the omissions were stunning.

Missing, for example, was the Gates Foundation—which began funding the School for Moral Ambition weeks before Bregman launched his media campaign promoting Gates’s philanthropic work.

It was almost by accident that I stumbled upon a link buried on the website, which opened a document listing Gates as a funder. Notably, it also included a number of other philanthropies associated with ultra-wealthy individuals.

One listed donor, Spectrum Impact, appears to be a project of billionaire chemical tycoons Chandrakant and Rajendra Gogri. The Porticus Foundation reports its funding comes from “the charitable entities established by the Brenninkmeijer family business owners”—which appears to the family behind a notoriously secretive multi-billion-dollar fast-fashion business empire.

The Gates Foundation’s wealth, meanwhile, comes from Gates’s investments in Microsoft, one of history’s most destructive tech monopolies. Less well understood is that Warren Buffett has given to the Gates Foundation $40 billion, the source of that money being Buffett’s giant investment firm Berkshire Hathaway, which currently has $26 billion invested in fossil fuel giants Chevron and Occidental Petroleum. Buffett is also the poster child for billionaire tax avoidance—paying a ‘true tax rate’ of .10% some years, according to a ProPublica analysis.

How do we square these donors with Bregman’s public excoriation of the ill-gotten gains and tax avoidance that fuel billionaire philanthropy?

The website of Bregman’s School for Moral Ambition, very notably, barely mentions taxing the wealthy; the only brief mention I could find on taxes was a passing reference to “tax evasion,” a distinctly different issue from the legal tax avoidance billionaires engage in through loopholes and legal maneuvers.5

There are other questions we should consider. How can we be sure, at this point, that we now have the complete list of funders? In what other ways might Bregman, his book or his non-profit promote the interests of his non-profit’s funders—or carefully avoid criticizing them?

What’s particularly troubling is that Bregman and his team show no sense of accountability or humility when confronted, offering no meaningful admissions, corrections or apologies. When I contacted Bregman’s agent about my discovery of Gates’s funding, she dismissed any wrongdoing. “There is no secret or hidden funding,” Strunk noted.

Really? Why wasn’t Bregman clearly, prominently disclosing his ties to Gates during his media campaign promoting Gates? Why wasn’t he shouting it from the rooftops? And why, when asked directly for a list of funders, did Bregman’s non-profit fail to disclose Gates’s funding? If there’s nothing to hide, why has Bregman’s group made it so incredibly difficult to follow the money?

Elsewhere in the email, Strunk offered a slightly different response: “We agree that this information should be more visible, which is why we’re in the process of redesigning our website.” She also said the non-profit’s donors don’t influence its work.

A reasonable person could ask what else is being hidden in Bregman’s work, but when I tried to open this door, I didn’t get the engagement I was hoping for. I asked Bregman if he has any personal, financial interests (investments, work contracts, etc.), with any entity, that stands to benefit from the work of the School for Moral Ambition. The response I got—from Strunk—didn’t answer this question. Instead, I was told that Bregman has no personal, financial ties to Gates.

According to Strunk, the The School for Moral Ambition has received $75,000 from the Gates Foundation to date, which she quickly minimized as a tiny part of the non-profit’s budget.

There are four problems with this response.

One, the amount doesn’t really matter. The issue is about credibility.

Two, one can assume that Gates (and Bregman’s other donors) will continue to give money going forward— if Bregman’s non-profit does work that aligns with, or does not challenge, their interests. If Bregman continues to use his public platform to praise Bill Gates, for example, there’s every reason to believe a second, larger donation could be coming from Gates. Also notable (and stunning): Bill Gates reportedly has made personal financial investments in fake meat companies—and Bregman’s School for Moral Ambition has an entire program supporting ”the protein revolution,” which appears to mean promoting fake meat. This seems to present an extraordinary financial conflict of interest for both Gates and Bregman’s non-profit.

Three, $75,000 may not be a lot of money for Bregman or his multi-million-dollar non-profit group. But to the wider world, $75,000 is a very large sum of money. And if all of Bregman’s ultra-wealthy donors are giving $75,000, the total sum rises very quickly.

Four, there is no way to confirm or verify that $75,000 is the full sum. The non-profit would not provide a copy of its actual grant agreement with the foundation. The Gates Foundation does publicly report the $75,000 gift, but there’s no way to know if Gates is also giving money through other channels. (The foundation, as I show in my book, uses intermediaries to funnel money into groups in non-transparent ways.) This means we have to trust—and cannot verify—that Gates and Bregman’s reporting gives us the whole truth.

Through one lens, Bregman’s story could be read as another demoralizing anecdote about the awesome financial power of billonaires, who can use their wealth to carefully and willfully co-opt many, if not most, of their would-be and should-be critics. The Gates Foundation’s expansive funding of newsrooms, for example, has hurt the independence and integrity of many news outlets, diminishing their ability to put a critical lens to the foundation’s destructive, anti-democratic influence. The same is true of the billions of dollars Gates is giving to universities, where researchers have coined the term “the Bill chill” to describe the reluctance of many scholars to bite the hand that feeds them.

The fact that one of the most widely cited critics of billionaires is now financially partnering with Gates and other billionaires—this is a very, very bad thing.

But through another lens, Bregman’s story can be read with less of a sense of loss. Bregman was never a novel or groundbreaking thinker or writer on billionaires or taxing the wealthy. He’s a guy who had the privilege to be invited to the World Economic Forum, the smarts to make a modest but very good critique about taxing the wealthy, and the ego and ambition to continually push his voice into the debate on extreme wealth in the years ahead. It is unfortunate and troubling that Bregman today almost seems to be becoming the archetype he once villified—the arrogant, tax-avoiding, wealthy, “bullshit” philanthropist. But it perhaps should not be surprising.

Early reviews have described Bregman’s idea of “moral ambition” as a conceit by and for the global elite. The Guardian reports that Bregman’s book is written for entitled, privileged “high-flyers” and is likely to draw criticism around “white saviorism.” The headline of Jacobin’s review offered a similar take: “Rich and Successful Enough to Be Moral.”

According to the The Guardian, Bregman argues in his book that ‘to make a difference, you have to create something like a cult.’ He certainly seems well on his way with his ‘moral ambition’ project—-releasing a book, launching a non-profit, leaning on billionaires and taxpayers to subsidize his vanity project, and creating us-versus-them language that castigates his disbelievers as “noble losers.”

Bregman’s ‘moral ambition’ suite of products launch in the United States next week. Buyer beware.

Many people who do what Bregman does—-publicly present opinions and publish writing aimed at a public (non-scholarly) audience—-studied history in college and cite history in their work. But they don’t call themselves historians. Former Fox News anchor Bill O’Reilly is one example. Bregman, by calling himself a ‘historian,’ takes on the air of a serious intellectual, not merely a writer of popular books.

His one-sided assessment of the Gates Foundation raises additional questions about his calling himself a historian. When asked about his qualifications—about his scholarly contributions to the field of history or whether he has a PhD—Bregman’s agent told me, “Rutger is a historian by training and profession, with multiple internationally recognized books to his name. Like many prominent historians, he does not hold a PhD, which is not a requirement to publish serious historical work.”

I’m not the first person to question Bregman’s self-appointed title of historian. As the Deccan Herald wrote of his previous book, “Bregman, despite what his Wikipedia page claims, is not a historian. He is a polemicist. ‘Humankind: A Hopeful History" is not a work of serious historical scholarship. It is a manifesto. It uses historical scholarship insofar as it serves the political goals of the book.”

There are no hard and fast rules defining a historian, but professional historians are exepcted to follow standards of professional conduct, including around integrity, mutual respect, and managing financial conflicts of interest. According to the American Historical Association:

“Historians should…avoid situations in which they may benefit or appear to benefit financially at the expense of their professional obligations…. Historians should acknowledge the receipt of any financial support, sponsorship, or unique privileges (including special access to research material) related to their research, especially when such privileges could bias their research findings. They should always acknowledge assistance received from colleagues, students, research assistants, and others.”

The first author of the article, Saloni Dattani, works for the Gates-funded Our World In Data. The second author, Rachel Glennerster, has worked on a number of Gates-funded projects over the years, including the Poverty Action Lab and, today, the Center for Global Development. Neither author made any disclosures in the article about their ties to Gates. They also did not respond to repeated press inquiries.

Gates also doesn’t look great in an earlier, related investigation by ProPublica, which the New York Times, oddly, doesn’t appear to cite in its reporting.

The school’s calculator appears to describe tax benefits to donors in Europe. Tax scholars have shown that wealthy donors in the United States, by contrast, can generate as big as a 74 percent tax break from their charitable gifts. That means that every dollar that a billionaire gives to charity saves them as much as 74 cents in taxes they would otherwise have to pay. The result is that the rest of the tax-paying public is effectively subsidizing the giving of billionaires.

Painfully, Bregman last year promoted Bill Gates as a progressive voice on taxation.

As I report in my book—an entire chapter of which is devoted to taxation—Gates tends to promote taxes that don’t apply to his own fortune. Also, the multi-billionaire has avoided billions of dollars in taxes through philanthropy.