Is philanthropy profiting from genocide?

The Gates Foundation's endowment has invested $16 billion in companies that divestment campaigns link to Israeli occupation, displacement and ethnic cleansing in Gaza

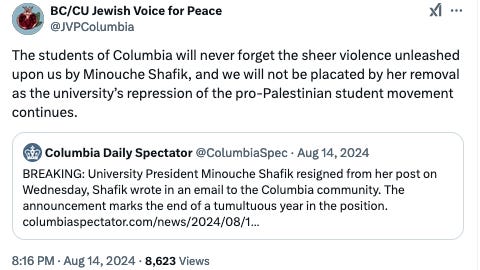

One of the most visible demonstrations of resistance to the ongoing genocide in Gaza are the student protests aimed at pressuring universities to divest their endowments from companies complicit in Israel’s war machine. Nowhere have demonstrations perhaps been more impactful than at Columbia University, where the school’s now-former president Minouche Shafik aggressively sought to crack down on protests.

“When I think of Shafik in the years to come,” Palestinian student Maryam Alwan told The Nation, “The images that will flash in my mind will be of bloodied students dragged out in handcuffs amid screams, of hundreds of armed riot cops storming campus in the dark, of locked gates devoid of community within, and of the blood spilled in Gaza with weapons she refused to cease investing in at all costs.”

It was a sentiment that echoed widely across—and beyond—Columbia University.

Shafik’s embattled tenure at Columbia—she resigned after only one year in the position—was marked by widespread criticism around her views on free speech and human rights. But this criticism, notably, had no impact on her other prominent professional position—at the Gates Foundation, where she sits on the board of trustees.

And that’s because the world’s most celebrated humanitarian body has no moral position, or moral compass, on the world’s most pressing humanitarian crisis.

While the foundation publicly condemned the “horrifying terrorist attacks in Israel” in October 2023, it does not appear to have ever condemned, or even mildly criticized, the actions of Israel, which a growing body of experts and human rights groups today say is committing war crimes, genocide and ethnic cleansing in Gaza.1 Even after a cease fire deal was announced this week, which would finally allow needed humanitarian aid to enter Gaza, Israel continued to launch attacks, killing 77 Palestinians, according to Reuters.

A press inquiry to the Gates Foundation asking for clarification on its position on Gaza generated no response. The foundation’s public records, meanwhile, show less than $10 million in charitable donations—from its $76 billion endowment—toward humanitarian help in Gaza over the last 15 months.

As millions of civilians have been killed or displaced—whether through bullets, bombs, disease or privation—the Gates Foundation’s silence and inaction is difficult to square with its humanitarian mission to save lives. But this silence appears to align with the foundation’s financial interests—the $16 billion it has invested in companies targeted by divestment campaigners on university campuses.

This includes the stocks and bonds the foundation’s endowment holds in a wide array of weapons manufacturers: Boeing ($16 million), Rolls Royce ($12 million), BAE ($11 million), RTX ($7 million), Northrop Grumman ($3 million), Lockheed Martin ($2 million), General Dynamics ($2 million), and L3Harris ($2 million).

The Gates Foundation’s financial records also show $2 million invested in Chevron, a company the American Friends Service Committee targets for divestment because it is “fueling and exploiting the military blockade of Gaza.”

Some divestment campaigns target companies that the Who Profits Research Center cite as being involved in “the ongoing Israeli occupation of Palestinian and Syrian land and population.” Screening the Gates Foundation’s endowment with this database turns up investments in Toyota ($142 million), Hitachi ($67 million), Sony ($33 million), Ford ($28 million), General Motors ($10 million), Teva ($11 million), IBM ($1 million), and Volkswagen ($1 million).2 (The Who Profits Research Center provides detailed explanations of why each of these companies is included in its database, if you want more details.)

Most divestment campaigns also target Caterpillar, citing reports that the company’s heavy machinery is used by Israel to commit human rights violations. Over the last year, Norway’s largest pension fund and Alameda County (home to Oakland, California) divested from Caterpillar for this reason. The Gates Foundation, meanwhile, remains one of the company’s largest shareholders. The value of the foundation’s seven million shares have skyrocketed since Israel launched its assault on Gaza—from $1.8 billion to $2.9 billion.

The foundation’s largest investments targeted by divestment campaigns are found in the tech sector, including small holdings in Alphabet ($330,000) and Amazon ($7 million), and a massive $12.5 billion stake in Microsoft. Journalists, researchers and activists have published extensive reporting on how Microsoft, as Mondoweiss described it in 2021, “benefits from, and contributes to, Israeli militarism and violence.”

It’s a critique also being levied by some of Microsoft’s own employees who have banded together under the name No Azure for Apartheid, a self-described “group of technology workers within Microsoft and its subsidiaries seeking to expose and condemn the specific technologies complicit in the ongoing apartheid and genocide in Gaza, the West Bank, and Palestine as a whole.”

One would expect similar protests from employees and grantees of the Gates Foundation, given the organization’s humanitarian mission around saving lives—and given the death toll in Gaza, which includes an estimated 18,000 children. Yet I could find no public record of any foundation employee or grantee resigning, relinquishing funding, or speaking out about the philanthropy’s silence or complicity on Gaza. (If insiders want to speak out and are afraid of repercussions, my door is open, and we can talk off the record.)

For the Gates Foundation, it is difficult to overstate the importance, or power, of its investment activities—which are arguably far more impactful than its philanthropic giving. In the foundation’s most recent, public-facing financial records, from 2023, the foundation reports generating more than $11 billion in investment income. That’s almost twice the sum of money the foundation gave away in charitable grants the same year, $6 billion.

It’s worth re-reading this: in 2023, the Gates Foundation, which supposedly is in the business of giving money away, generated almost twice as much investment income as it donated in charitable grants.

If the world’s most revered philanthropy were to divest $16 billion from its endowment, this would send a powerful global message challenging the moral authority and political support Israel depends on to continue its ethnic cleansing. The obvious question to ask: is Bill Gates really going to direct his foundation’s trust to divest from the company he founded, Microsoft? Probably not.

However, the foundation might be moveable on other fronts, like its investments in weapons manufacturers. Or who it asks to sit on its board of directors (and who it asks to leave). There is a precedent to consider.

In 2014, more than 100 international organizations called on the Gates Foundation to divest its $176 million stake in the security company G4S, arguing that the foundation was “legitimising and profiting from Israel's use of torture, mass incarceration and arbitrary arrest to discourage Palestinians from opposing Israel's apartheid policies.” The foundation initially pushed back on criticism, saying its investment decisions are organized around one goal, making sure the “foundation has the most money possible to support the great work the foundation does with partners around the world.”

While many philanthropies have long recognized that their investments should align, morally and ethically, with their charitable missions, the Gates Foundation has always advocated a different position—essentially, that the more money the foundation makes (no matter the source), the more good it can do through charity. The foundation’s ends-justifies-the-means ethos, however, has limitations.

Once Western news media began reporting on the divestment campaign Gates faced around G4S, the foundation quickly changed directions, selling off its shares. That shows the foundation is vulnerable to public pressure. While the philanthropy may not have a moral conscience, it is extremely sensitive to bad press. (This also explains the foundation’s expansive financial ties to journalism, including hundreds of millions of dollars in donations to outlets around the world—- NPR, The Guardian, El Pais, Le Monde, Der Spiegel and dozens of others.) Unless or until activists and journalists begin drawing attention to the Gates Foundation’s endowment, we should not expect the foundation to change directions.

It’s almost surprising that divestment campaigns have not yet confronted Gates given the sums of money in question. Student protesters at Columbia University only targeted the school to divest a few million dollars—an order of magnitude smaller sum than the $16 billion found at the Gates Foundation.3

While some voices in American philanthropy—which has more than a trillion dollars in assets— have spoken out about divesting and genocide, these campaigns include no really big funders, certainly nothing at the level of a Gates, Ford, Lilly, Rockefeller, Hewlett, or MacArthur.4 When I followed up with these philanthropies, asking about their positions on Gaza and about divestment, I received no responses.

Only one large philanthropy did respond. The Wellcome Trust, which boasts a $46-billion endowment, told me by email, “Wellcome is a politically and financially independent global charitable foundation. We support science to improve health. In line with our charitable purpose and mission, it is not our role to take a position on international conflicts, or in delivery of humanitarian relief support.”

The UK-based philanthropy sidestepped questions about divestment and refused to provide full details of its investment portfolio, meaning we can’t know to what extent Wellcome may be positioned to financially benefit from genocide. The philanthropy’s limited public reporting (of its top 35 public equity holdings) shows more than two billion dollars invested in companies that have been targeted by divestment campaigners on university campuses— Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft, Cisco and Siemens.

The silence, inaction, investment, or complicity of the world’s most prominent philanthropies on the genocide in Gaza should raise sharp questions about their legitimacy as public-good institutions, their claims to the title of humanitarianism, and their growing political power. Today these massive, multi-billionaire non-profit philanthropies wield enormous influence over all of our lives, radically shaping our public health, our public education, and our climate response. But they do so from a place that often seems bereft of the most basic morals, values and ethics that define humanity.

The institution of billionaire philanthropy, and the Gates Foundation in particular, is in dire need of a major overhaul, if not dismantling, and the genocide in Gaza gives us a rare opportunity to mount such a challenge. Isn’t it time that we confront the Gates Foundation, and its peers, with a simple question: should humanitarian bodies be positioning their endowments to generate investment income from genocide?

Isn’t it time we call on philanthropists and humanitarians to divest?

A United Nations Special Committee has said Israel’s actions are consistent with genocide, a UN Special Rapporteur has called Israel’s actions a genocide, Amnesty International has concluded that Israel is committing a genocide, and Human Rights Watch says Israel’s activities appear “to meet the definition of ethnic cleansing.” In addition, the International Criminal Court has issued an arrest warrant for Israeli leader Benjamin Netanyahu, who is accused of committing “crimes against humanity and war crimes.”

My analysis includes Gates Foundation investments in parent companies. For example, I included the foundation’s investments in Ford Motor Company and Ford Motor Credit Co in the tally for Ford. I excluded from my analysis Gates’s investments in various companies bearing the name Hyundai ($129 million) and Mitsubishi ($405 million) because they did not match the specific corporate names appearing in the Who Profits Research Center database—HD Hyundai and Mitsubishi Motors.

To be fair, many university activists have been stymied by a lack of transparency. As an example, one student-led proposal for divestment at Columbia University only uncovered only a few million dollars invested in companies linked to genocide, but added a caveat: “We note that Columbia likely has many more indirect investments in companies supporting Israeli settlements, but most investments are not readily available in public documents.”

Hundreds of Jewish donors have condemned their philanthropic peers who decided to cut off support for organizations that criticize Israel or support Palestine. Likewise, Funders4Ceasefire.org has sought to push philanthropies to divest their endowments, to sign an open letter calling for a cease fire, and to direct resources to Palestinian organizations. None of the largest philanthropic funders, however, appear to have been confronted about their positions on Gaza.